![]()

George Harrison once distilled the Beatles’ origins with characteristic precision, tracing their musical lineage to the deep well of the blues. “If there was no Lead Belly, there would have been no Lonnie Donegan; no Lonnie Donegan, no Beatles,” he remarked, as recalled in The Legend of Lead Belly. Yet Donegan’s skiffle wasn’t just a spark for British rock; it drew from the rolling cadences of country, the twang of bluegrass, and the folk traditions of old-timey ballads.

Liverpool, in those formative years, boasted a lively country music scene, with figures like Phil Brady holding sway. While the Merseybeat explosion often takes center stage in Beatles lore, these quieter strains of influence—country and western in particular—left a lasting mark, one that would bloom more fully as the group evolved.

For John Lennon, country music wasn’t a distant echo but a formative experience. “I grew up with blues music [and] country and western music, which is also a big thing in Liverpool,” Lennon later reflected. His first encounter with a guitar came not through rock but via the Hawaiian slides of a cowboy-clad street performer in Liverpool. It was a vision that lingered, shaping the Quarrymen, Lennon’s pre-Beatles outfit. String ties, a nod to the rakish charm of Maverick star James Garner, completed their image as purveyors of skiffle, country, and rock 'n' roll.

When the Quarrymen transitioned into the Beatles, those rootsy inclinations didn’t vanish. Early auditions, like the one for BBC Radio producer Peter Pilbeam, earned the band a distinctive label: “I wrote that they were 'an unusual group not as rock-y as most, more country and western with a tendency to play music,” Pilbeam noted, marking them as a group unafraid to stray from the raw noise of their peers.

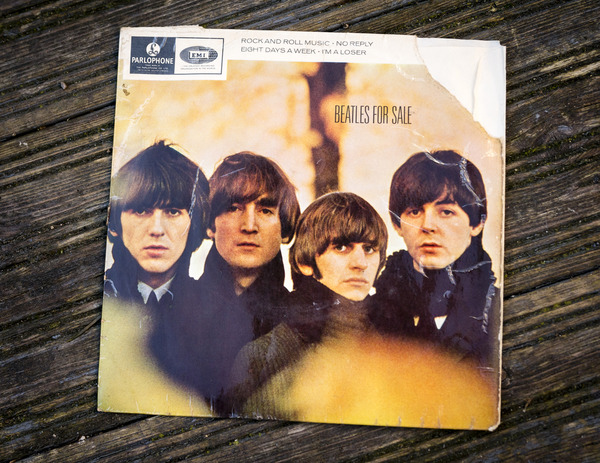

By the time Beatles for Sale arrived in December 1964, the group was ready to showcase their roots in earnest. Tracks like “Baby’s in Black” and “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party” bore the unmistakable twang of country, with Lennon and McCartney embracing the genre’s plaintive storytelling and mournful harmonies. Paul McCartney later described the latter song as a deliberate nod to western balladry, with George Harrison delivering a guitar solo steeped in Nashville stylings.

Even the covers on the album—Carl Perkins’ “Honey Don’t” and “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby”—reflect the influence of the American South. For Ringo Starr, who took lead vocals on “Honey Don’t,” it was a natural fit. “We all knew 'Honey Don't'; it was one of those songs that every band in Liverpool played," Starr said in Anthology. "I used to love country music and country rock."

Beatles for Sale marked more than a nod to nostalgia; it unlocked a broader palette for the group. Tracks like “Act Naturally” on Help! and “What Goes On” from Rubber Soul continued this exploration, their rhythms and picking styles indebted to country’s traditions. Starr’s eventual solo project, Beaucoups of Blues (1970), further solidified the Beatles’ ties to Nashville.

For Lennon, the genre remained a touchstone even in his solo work, with tracks like “Tight A$” exuding country charm. McCartney, too, dabbled with the wistful tones of “Country Dreamer.” And now, with Starr’s upcoming Look Up (2025), co-written with T Bone Burnett, the legacy of Beatles for Sale continues to reverberate, a testament to the band’s ever-expanding musical vision.

In Lennon’s words, Beatles for Sale might well have been their “country and western LP.” If not entirely true, it at least hinted at the far-reaching influences that shaped the Beatles—and, in turn, reshaped the landscape of popular music forever.